Softshell turtles are unlike any other group of turtles – with their soft-shells, snake-like neck, and snorkel-like nostrils. Native to Africa, Asia, and North America, this group (family Trionychidae) contains 35 species. Three species of softshell turtle are found in North America. The Florida softshell (Apalone ferox) is the largest. In Florida, I have had dozens of encounters with this species, including observing an interaction with an alligator that I posted about previously. These encounters prompted me to learn about this species, and ponder what selection pressures have favored a soft shell in turtles, and the exceptionally large size of the Florida softshell turtle in particular. This post is my exploration of these topics.

A few of the photos I have taken of Florida softshell turtles over the past few years.

The Florida softshell is the second largest freshwater turtle in North America, after the alligator snapping turtle. The largest recorded Florida softshell weighed a whopping 96 pounds. For comparison, the largest alligator snapping turtle on record was 211 pounds and the largest common snapping turtle found in the wild was 76.5 pounds. All three North American softshell species attain relatively large size with shell lengths of 14 inches (smooth softshell), 21 inches (spiny softshell), and 30 inches (Florida softshell). Yet, the giant softshell turtles of Asia are even larger. The Yangtze giant softshell turtle, thought to be extinct in the wild, could reportedly weigh over 500 pounds! This species is one of several species of giant Asian softshell turtles that reach over 200 pounds. Thus, large body size is a characteristic of the group.

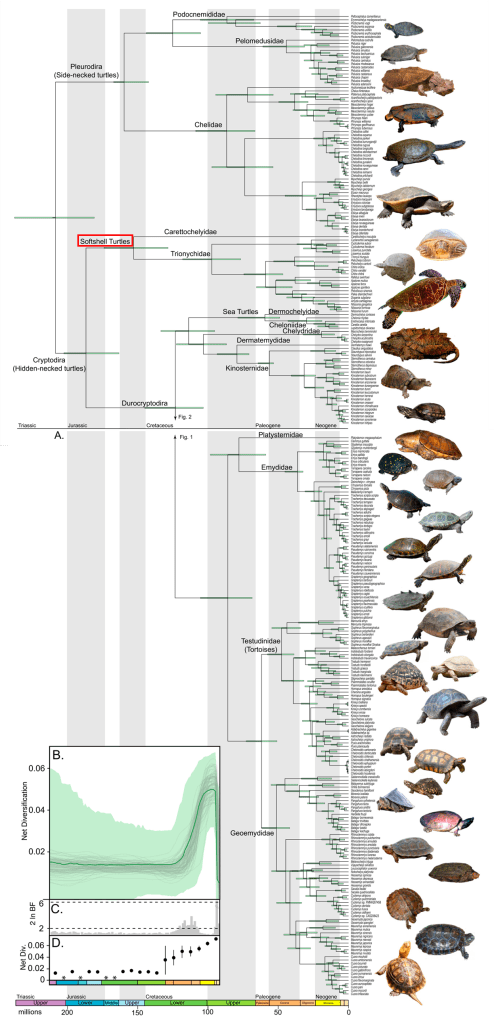

An evolutionary tree of turtles, taken from Thomson et al. (2021). The softshell turtle clade is indicated in red.

Evolutionary tree of softshell turtles, from Timetree.org. The most closely related ‘outgroup’ to the softshell turtles is the pig-nosed turtle, native to northern Australia and southern New Guinea. The Florida softshell turtle is indicated with a red star, one of three North American species in the genus Apalone. Three species of Asian giant softshell turtles, which can reach over 200 pounds, are indicated with black stars.

An obvious question to ask is: Why did a soft shell evolve in turtles? In other words, given the protective function of a hard shell, what are the selective advantages of evolving a soft shell? One thing to note is that the outer soft shell of softshell turtles is tough and leathery, not soft and squishy . Furthermore, they still have a layer of bone underneath their leathery exterior. Additionally, they have long extendable necks and a sharp beak-like mouth. Finally, as noted above, they attain relatively large size. All this is to say that despite being soft-shelled, they are fairly formidable turtles and are not defenseless. As adults they probably have few natural predators, save humans, across much of their range. One exception to this, in the southern USA, is alligators – a point I will return to at the end.

Softshell turtles are well adapted to an aquatic lifestyle. Their shells are both soft and relatively flat, and it is worth considering the costs and benefits of both features in relation to their lifestyle and habits.

Domed vs flat shells

There are numerous tradeoffs associated with turtle shell shape (refs 1, 2, 3). Two advantages of a domed shell are greater structural integrity and an easier ability to self-right. Specifically, a more domed shell can withstand greater crushing force than a flatter shell. And if flipped on its back, a turtle with a domed shell can more easily right itself. A disadvantage of a domed shell is the lack of streamlining, and hence slower locomotion in water and/or on land. Another disadvantage is that a domed shell exhibits a larger surface area than a flatter shell of the same size profile and hence is more costly to construct.

Contrasting shell shapes in Galapagos tortoises from different islands. The domed shell shape is associated with islands containing dense vegetation, and the saddleback shape with drier islands. This is likely to be adaptive. A domed shell could be advantageous for bulldozing through dense vegetation by increasing streamlining, while the greater neck reach of the saddleback shell would allow access to elevated shrubs when grazing. Photo credits: (1) Matthew Field, (2) Just Janza.

An alligator attempts to crush a Florida Red-bellied Cooter (Pseudemys nelsoni) in its jaws. It was unsuccessful and the turtle escaped. I took these two photos one second apart. Alligators have one of the strongest bite forces in the animal kingdom: 2,000 pounds per square inch (PSI). For comparisons, lions have a bite force of 600 PSI and humans 120 PSI. Yet when such force was applied to this turtle it slipped out of its jaws. I suspect the domed shell of the turtle strongly contributed to its survival, and a flat shelled turtle would be more likely to be crushed. This interpretation is supported by a study of River Cooters (Pseudemys concinna) which compared shell characterisitics of two populations in Alabama, one coastal population where alligators were present, and one inland population outside the range of alligators. 59% of adult turtles from the coastal population had alligator bite marks on their shells. They also had higher arching shells with the authors concluding “a highly arched shell may protect lower Gulf Coastal Plain populations of P. concinna from predation, especially when attacked by alligators in the smaller or medium size classes.”

Turtles and tortoises are notoriously slow moving. However, softshell turtles are consistently described as the fastest running turtles (not a phrase typically associated with turtles). This is probably no coincidence. The soft shell is lighter than a hard shell and the flattened shape makes them more streamlined. Undoubtedly, both contribute to the speed at which softshell turtles can run on land and swim in strong river currents.

Softshell turtles are surprisingly fast runners.

Another advantage of a flattened pancake-like shell shape for aquatic turtles is that it can aid in concealment amongst the bottom substrate. Softshell turtles frequently bury in the sand or mud on the lake or river bottom. They can then extend their necks to the surface with only their snorkel-like nostrils above the water, while their body remains concealed underwater. This concealment amongst the bottom substrate is also seen in some flatfish such as flounder.

Spiny softshell turtles (Apalone spinifera) buried in the bottom substrate, similar to how flatfish such as flounder conceal themselves, as seen in the last photo. Photo credits: (1) Todd Pierson, (2) Phillip Colla, (3) & (4) Dave Coulson, (5) Andrew J. Martinez.

Hard versus soft shells

As far as I can tell, the primary advantage of a hard shell is greater protection from predation. And the primary disadvantage is that hard shells require a long time to construct, hence turtles typically grow slowly and take a long time to reach reproductive maturity. That is, there is a tradeoff between growth and reproduction; investment of nutrients and minerals required to develop a hard shell cannot simultaneously be used for reproduction, and vice versa. Hence turtles have a notoriously slow life history, often taking decades to reach reproductive maturity. Therefore, a prediction would be that soft-shelled turtles exhibit faster growth and earlier maturity than hard-shelled turtles of comparable size. Is this supported? The Florida softshell reportedly reaches reproductive maturity at 2 years of age for males, and 5-8 years of age for females. The alligator snapping turtle reaches maturity around 12 years of age. The common snapping turtle reaches maturity at 12 years of age in southern populations and 15-20 years in northern populations. Hence, amongst this limited comparison of large North American freshwater turtle species, the life-history prediction appears to hold.

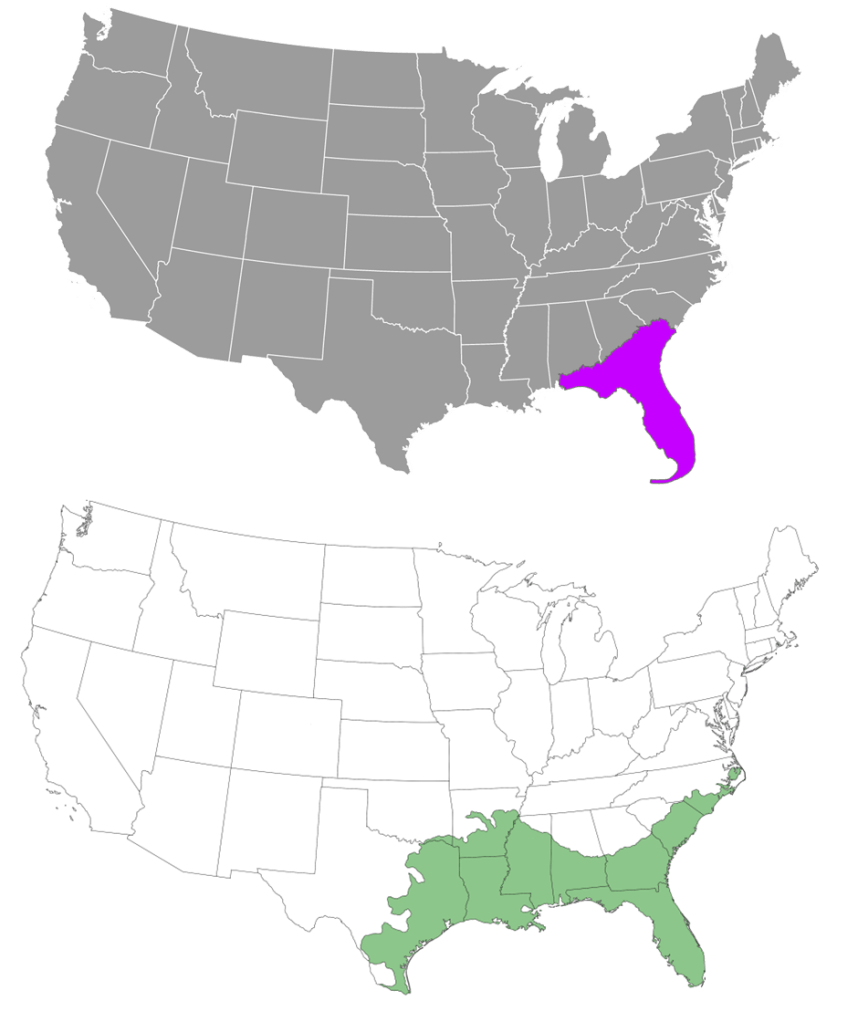

As discussed in a previous post, large alligators prey on turtles. To me it is interesting, and perhaps not coincidental, that the largest species of softshell turtle in North America (the Florida softshell) happens to entirely overlap in its range with American alligators.

The geographic range of the Florida softshell turtle (purple) is entirely within that of the American alligator (green).

I know from firsthand experience that smaller alligators do not view adult Florida softshell turtles as prey, as I have seen the two species basking next to each other and even swimming together. It seems possible that the large adult size of softshell turtles, in general, may be a way to insulate themselves from predation. A fast-growth rate and large adult size means they quickly outgrow the size at which they are susceptible to most predation, reaching a size refugia where only predators such as large alligators and humans could realistically prey upon them.

We can now put together the various points discussed above. It seems likely that softshell turtles have traded the protection offered by a hard domed shell for the streamlining (and speed) of a soft flat shell; they have traded slow growth and investment in heavy armor for fast growth and large size. Large size potentially insulates them from most predation, mitigating the reduced protection offered by a soft shell. Finally, their soft flattened shells and unique combination of features (i.e. long snake-like neck, snorkel-like nose, webbed feet, penchant for burying in bottom substrate) appear well adapted for an aquatic lifestyle.

Awesome article and incredible photography!

LikeLike

interesting correlation.

LikeLike

Very interesting creatures! Love seeing them swim around

LikeLike