An interesting new paper describes how a diet composed almost entirely of fish and caiman (a relative of the alligator) has likely allowed jaguars in the Pantanal, Brazil’s vast wetland, to reach high population density, caused territorial breakdown, and led to unexpected social interactions (cooperative fishing, co-traveling, and playing) between unrelated adults.

Across most of their extensive geographic range, from southern Arizona all the way to Argentina, jaguars are found at low population density, prey and feed largely on mammals, and are primarily solitary. The Pantanal is a vast seasonal wetland found in Brazil. Here, jaguars break all these rules. In the Pantanal, jaguars are found at the highest density of anywhere else in their range. If you want to see jaguars in the wild then this is the place to go.

The new paper by Eriksson et al. (2021) examined the density, diet, and social interactions of jaguars in the Brazilian Pantanal. The authors used an extensive system of camera traps and GPS collars, fitted on a subset of 13 individuals, in order to estimate the density of jaguars. Individual jaguars were able to be identified on the camera trap images and videos based on their unique coat patterns. They estimated the population density at 12.4 individuals per 100 square kilometers, which is the highest density estimate to date. For comparison, jaguar density has previously been estimated at 4.5 jaguars per 100 km2 in the Peruvian Amazon, 4.4 jaguars per 100 km2 in the Venezuelan Llanos, and 6.7 jaguars per 100 km2 in the drier southern Pantanal. A natural question is what is supporting such high jaguar population densities in the Pantanal? And what are the consequences of such high density for social behavior?

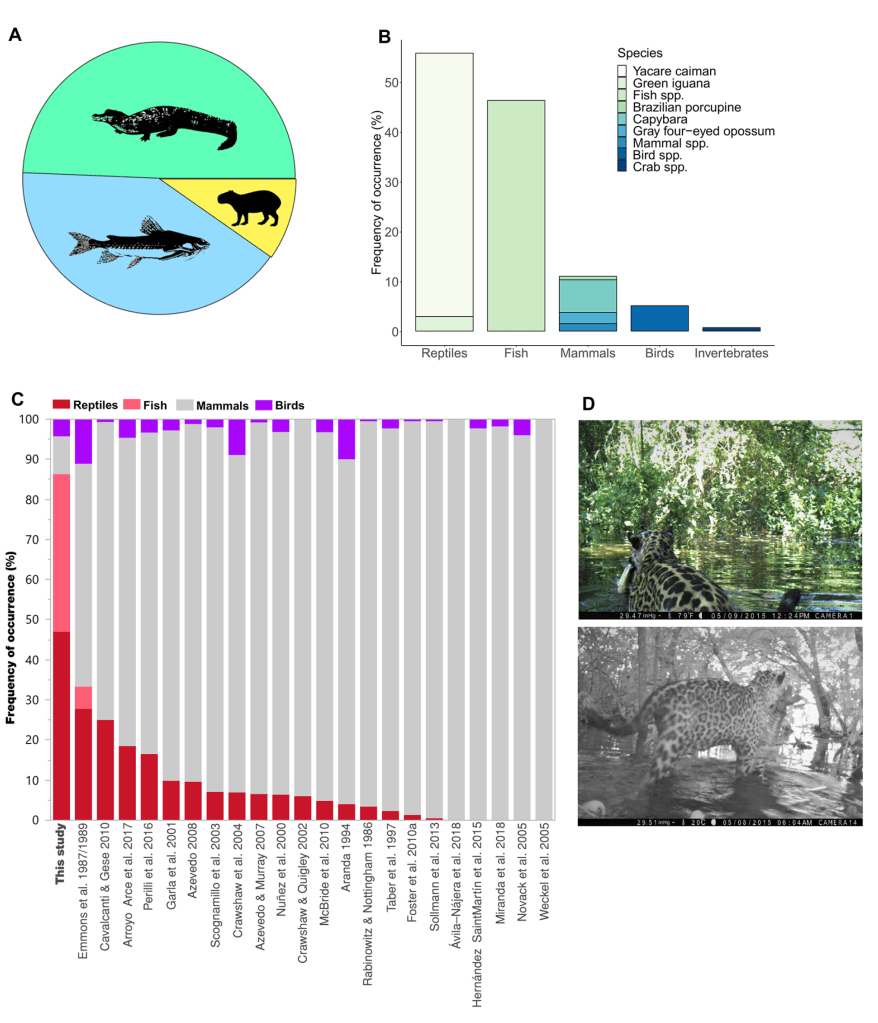

The authors examined the diets of this jaguar population. By examining 138 jaguar scats (i.e. droppings) the authors found a diet dominated by fish and aquatic reptiles. Specifically, 46% of scats contained fish, 55% contained reptiles (almost entirely caiman), and only 11% contained mammal remains (mostly Capybara). As the authors state: “Jaguars in Taiamã [the Pantanal study location] have by far the most aquatic diet and the least mammal consumption of any previously studied population. Although jaguars in Taiamã consume more aquatic reptiles than has ever been observed, it is fish consumption that makes this population truly unique. As far as we know, this is the most piscivorous diet of any large felid and among the most for any terrestrial hypercarnivore. Even the tigers (Panthera tigris) in the Sundarbans mangroves of India still consume mostly terrestrial mammals.”

“Fish remains found in the scats could not be identified to species, however, the camera data revealed jaguars capturing thorny catfish (Doradidae), pacu (Piaractus mesopotamicus), red-bellied piranha (Pygocentrus nattereri), and large tiger catfish (Pseudoplatystoma fasciatum).” –Eriksson et al. (2021)

Finally, the authors investigated social interactions and shared space use among jaguars by examining jaguar location data as assessed by both GPS collar data and camera data. With GPS data, interactions were defined as when two GPS-collared jaguars were within 200 meters of each other. With camera data, interactions were defined as when two jaguars were observed together or within 30 minutes of each other on the same camera trap. Home-range overlap was extensive for both male and female jaguars. 80 independent social interactions between adult jaguars were observed. These were mostly between males and females (68 interactions involving 29 individual jaguars) but also involved interactions between males (11 interactions involving 8 males) and females (1 interaction involving 2 females). The social interactions sometimes involved adult jaguars moving together for extended periods, fishing together, and even ‘playing’ in front of a camera.

So what is the link between this unique and specialized aquatic diet, high densities, and modified social interactions in this jaguar population? Aquatic ectotherms (i.e. fish and reptiles) are capable of reaching high levels of abundance because they are energetically inexpensive to produce (relative to endotherms such as mammals) and have high rates of reproduction in highly productive aquatic habitats. In the paper, the authors note that caiman, for example, are large-bodied (~50 kilograms) and reach population densities of over 50 per km2. The authors hypothesize that this resource-rich aquatic environment supports many more jaguars with smaller home ranges compared to other habitats. Furthermore, if prey are patchily distributed, as is often the case with aquatic animals, then the benefits of social tolerance of other jaguars outweighs the costs of local competition. The authors make an interesting parallel with brown bears: “Salmon systems famously support hyperabundant bear (Ursus arctos) populations with modified social dynamics due to the need to tolerate conspecifics at point sources (e.g., waterfalls and streams) where salmon become accessible.”