Caecilians are fascinating creatures. Within the Class Amphibia, they have their own Order (Gymnophiona) and are much less well known or studied than their cousins the frogs and toads (Order Anura), and salamanders and newts (Order Caudata). There are 215 recognized species of Caecilians (AmphibiaWeb).

The Caecilians are depicted in purple. Tree credit: AmphibiaWeb

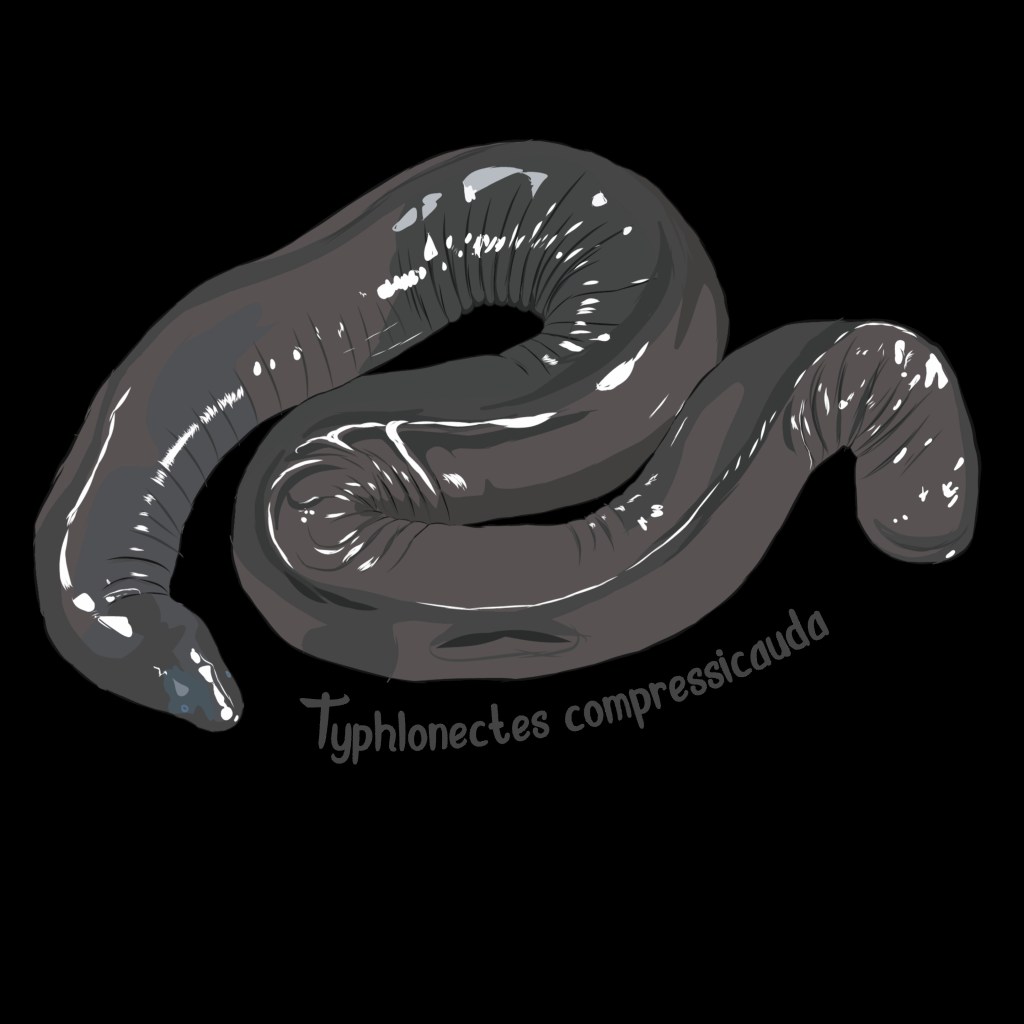

All caecilians are legless with very small eyes, and range in size from a few inches to five feet. The vast majority of species are terrestrial and live a secretive underground burrowing life-style feeding on earthworms and other invertebrates. One particular family, containing 14 species, has an aquatic life-style and are known colloquially as rubber eels. Caecilians exhibit a diversity of different forms of parental care. All species have internal fertilization. About 25% of species lay-eggs which are then guarded by the mother until hatching and sometimes even after hatching (when the mother also provides food to her juvenile offspring in the form of sloughed off skin). The other 75% of caecilian species give live-birth to fully developed offspring. The geographic range of caecilians is limited to the tropics and no species are native to the United States.

Examples of different caecilian species. Click to enlarge. Illustrations by Udith Raj

Until recently, when I captured one in a minnow trap in a Miami canal, I had never before seen a live caecilian. A recent paper by scientists from The Florida Museum of Natural History and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission definitively identified the species found in Miami canals as Typhlonectes natans, an aquatic species native to Colombia and Venezuela. This identification was done using morphology and by sequencing the mitochondrial 16S gene and comparing it to that of other sequenced caecilian specimens on the genetic repository GenBank.

How did caecilians get to Miami? It is probably relevant that this particular species is the most common caecilian in the pet trade and is bred in captivity. Since individuals are most likely to be kept indoors in aquariums, accidental escape seems unlikely. Instead, the most likely colonization scenario may be deliberate release of unwanted captive animals into the canal. When did they arrive in Miami? The first official observation was in 2019. During a biological survey of Miami’s C-4 Canal, Florida Fish and Wildlife officers captured an odd-looking eel-like animal and sent the specimen to Coleman Sheehy, the herpetology collection manager at the Florida Museum of Natural History.

Besides caecilians, Florida has three other introduced amphibian species: the Cuban Treefrog, Greenhouse Frog, and Cane Toad. Each of these species is very common in and around Miami and I have seen and photographed them on numerous occasions.

However, the number of introduced amphibian species in Florida – only 4 – is dwarfed by the number of introduced freshwater fish species – 48 – and introduced reptile species – 52. I don’t have a good explanation for why so many fewer amphibian species have been introduced to Florida. Elsewhere in the world, there have been some well-known and ecologically damaging Amphibian introductions – cane toads in Australia and a variety of other places, bullfrogs in the western U.S., and African Clawed frogs on five continents. Only time will tell whether the caecilians of Miami’s canals will expand their range and have any discernable ecological impact, but for now they are an interesting and novel addition to the menagerie of introduced species found in South Florida.