For each of five years (2013, 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020) I have been fortunate to spend 3-weeks in Costa Rica conducting collaborative fieldwork with friends and colleagues from Wageningen University. Our latest paper resulting from this work, with co-authors Andres Hagmayer and Bart Pollux, has been published in the journal Freshwater Biology. This research, designed to test a hypothesis regarding the functional advantage of evolving placentation, involved snorkeling in a variety of rivers – both during the day and at night. The fieldwork itself was really enjoyable ‘work’ and here I will give an inside story behind the paper and also use it as an opportunity to include many fieldwork photos.

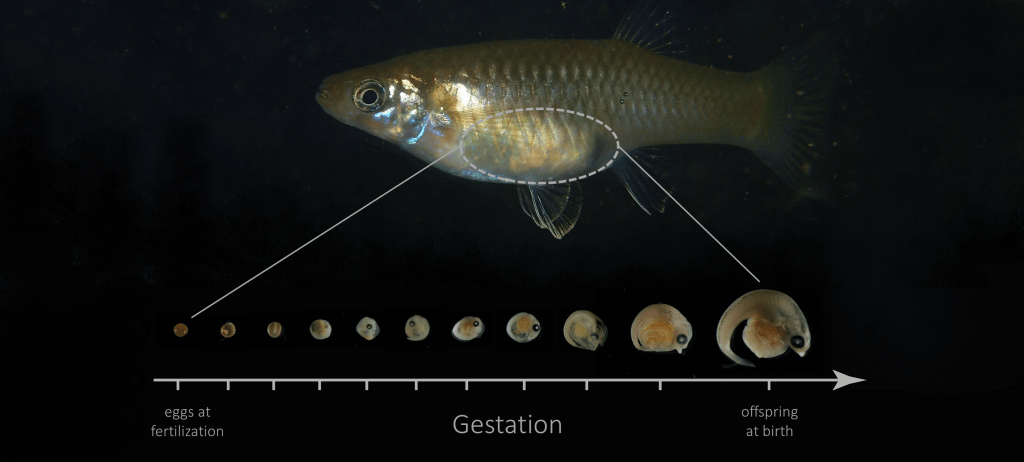

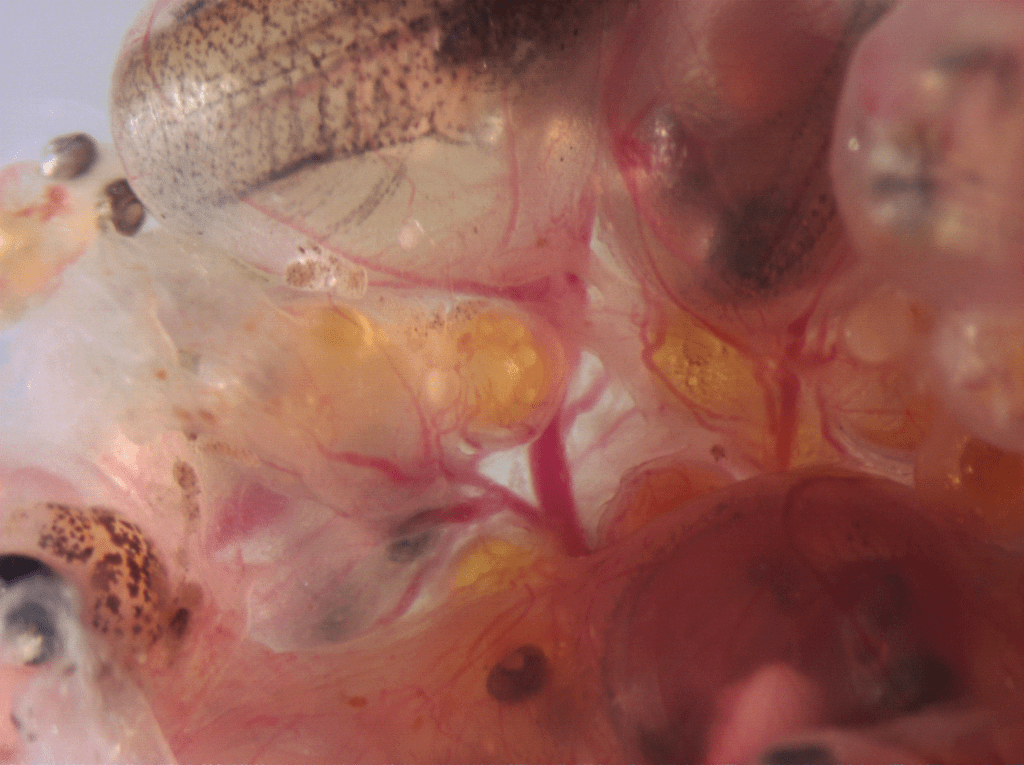

The fish family Poeciliidae contains 276 species of live-bearing fish distributed across much of North, Central, and South America, as well as Caribbean islands. This family includes well-known species such as the guppies, mosquitofish, sailfin mollies, and swordtails. All species in the family, save one, give live-birth to fully developed offspring. However, amongst live-bearers the mode of maternal embryo provisioning differs greatly. Most species in the family (~85%) are categorized as lecithotrophic or with ‘yolk nourished’ embryo provisioning. In such species, the mother fully provisions eggs with yolk prior to fertilization. Eggs thus start out large in size and, following fertilization, embryos decrease in weight over the course of gestation due to metabolic process. Thus, during pregnancy, the embryos are contained within the female ovary until she gives birth, but there is little to no maternal connection between the mother and offspring. In contrast, in matrotrophic or ‘mother feeding’ species, embryos start out tiny, with little yolk reserves. Over the course of gestation, embryos increase in weight due to nutrient transfer from the mother to the developing embryos. In poeciliid fishes, this is brought about by a follicular placenta. In some species in the family, embryos undergo a more than 100-fold weight gain over the course of gestation, before being born. Our prior work has demonstrated that matrotrophy by means of a follicular placenta has evolved independently multiple times in this family from lecithotrophic ancestors. Thus, the family is a good model system for studying the evolution of the placenta, as a case study in the evolution of a complex trait.

One important question under this broad umbrella research program is: why does the placenta evolve? In other words, what are the selective factors that have favored the repeated (and rapid) evolution of the placenta? Several hypotheses have been proposed. One is known as the locomotor performance hypothesis. It predicts that placentation evolves to facilitate locomotor performance of pregnant females in performance demanding environments. It may at first sound counterintuitive that the placenta may actually facilitate locomotion of pregnant females, and hence evolve for this reason. However, an analogy may be useful here. In humans, which of course are placental, eggs start out very small and offspring undergo a several thousand-fold weight gain over the course of gestation. For the first several months of pregnancy you generally cannot tell a woman is pregnant based on physical appearance. Likewise, locomotor performance is probably unimpaired during this period and it is only impaired in the late stages of pregnancy, when the offspring has gotten large in size. In contrast, imagine if a woman began pregnancy with a soccer-ball sized fully-yolked egg in her belly, and then went through a 9-month pregnancy. This is equivalent to lecithotrophic live-bearing, and in this case the mother would be predicted to bear a much greater locomotor performance-cost right at the outset of pregnancy, and lasting throughout.

This hypothesis thus predicts that pregnant females of lecithotrophic versus matrotrophic (i.e. placental) species will have different locomotor performance costs during pregnancy and may thus utilize different micro-habitats. Specifically, the advantage of having placentation as a mode of reproduction, compared to lecithotrophy, may be greatest in performance-demanding environments, such as rivers with a lot of current (i.e. high water flow velocity). This is because, strong flow may favor body streamlining and locomotor performance. Costa Rica is fairly unique in that there are multiple co-existing lecithotrophic and matrotrophic poeciliid species living in the same rivers and habitats. There are some other places where this occurs, particularly in Mexico, but overall this situation is rare. Thus, we wanted to test whether different co-occurring poeciliid species, that differ in reproductive mode (i.e. lecithotrophy versus matrotrophy), also differ in microhabitat usage in the field. Our prediction was that matrotrophic species would utilize faster-flowing waters than lecithotrophic species.

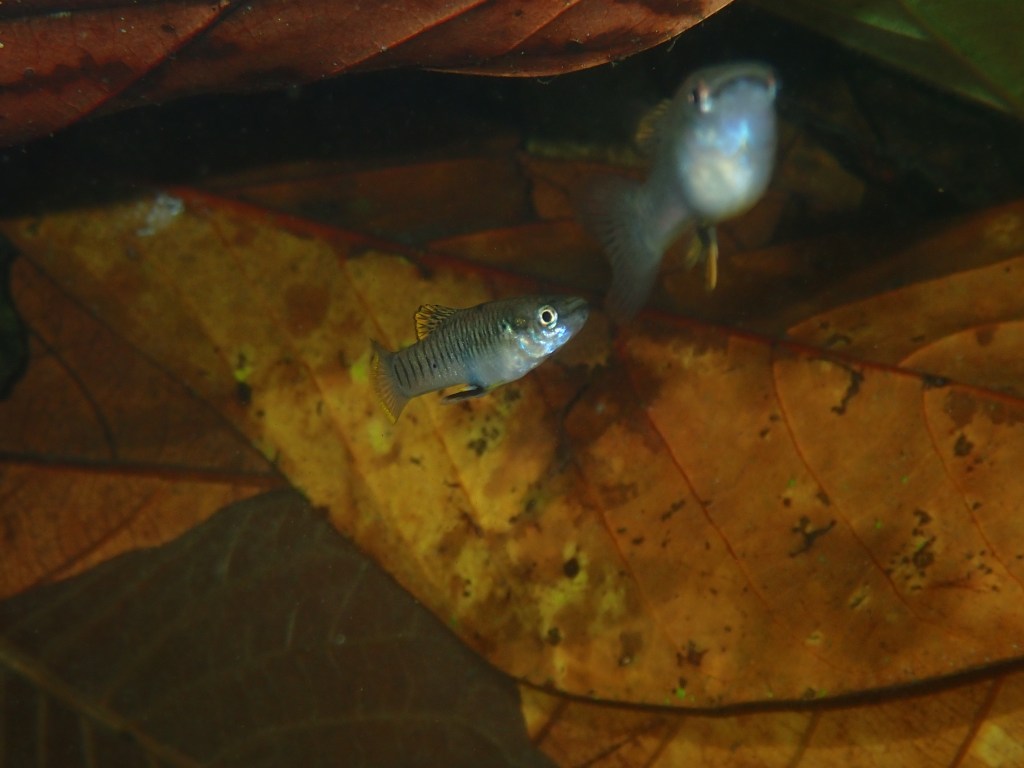

Early in our fieldwork, it became clear that the different co-occurring poeciliid species utilize different sections of the river and differ greatly in how easily they are caught (some of our other projects required us to capture each of these species). The five species we worked on were Poeciliopsis retropinna (matrotrophic), Poeciliopsis paucimaculata (matrotrophic), Poeciliopsis turrubarensis (lecithotrophic), Poecilia gillii (lecithotrophic), and Brachyrhaphis roseni (lecithotrophic). In particular, P. retropinna (as well as P. paucimaculata) adults were almost salmon-like in their ability to cut through very strong currents in the middle of the river. These species also proved very challenging to collect. After a particularly frustrating day trying to catch P. retropinna using a seine net in the fast-flowing current in the middle of a river while exposed to the full mid-day tropical sun, we thought there had to be a better way. I suggested we try visiting the site at night to see if this species might be easier to catch. This is what we did and it proved to be fruitful. At night the large P. retropinna adults, which were so difficult to catch in the middle of the river during the day time, were largely immobile resting / sleeping in the shallows. It was around this time that we decided to formally quantify habitat usage of all these species and also include a day-night component to capture this apparent habitat shift.

After thinking about and exploring several different experimental designs we decided upon one which co-author Bart Pollux had successfully employed in mangroves and coral reefs – visual transect snorkeling surveys. Our general approach was as follows. After finding a suitable river site, we set up a number of transects (two ropes running in parallel with 1 meter between them and meter marks on them). We set these up to encompass variation in flow, depth, and location in the river (i.e. next to shore, versus in the middle of the river). In essence we wanted to capture all the various microhabitats that each site had on offer. We then snorkeled each transect and identified all the poeciliid species and size classes (i.e. juvenile, immature, adult) present in each square meter of each transect and relayed this information to a data recorder standing by with pen and paper in hand. In very shallow transects (too shallow to snorkel), fish were instead identified from above while standing or sitting on the shore. Next, depth and water velocity were measured in the center of each 1m x 1m quadrat. The transects were left in place and we returned that same night and an identical procedure was repeated, except with the use of underwater flashlights and headlamps. This was repeated at 10 different sites, encompassing 143 transects, and 1,406 quadrats.

Transects and data collection in the rivers of Costa Rica.

It is always nice when the results of an experiment are so clear and obvious so as to not even need statistics to see the patterns in the data. The data analyses, conducted by Andres Hagmayer, couldn’t have been clearer. Andres is great at statistics and was able to conduct Bayesian habitat occupancy modelling which captured the clear results. During the day-time, we found that adults of the two matrotrophic species, P. retropinna and P. paucimaculata, were found in deep and fast-flowing waters, while adults of the lecithotrophic species were found in shallow, low-flow areas. There were no day-time habitat differences for juveniles of any of the 5 species – they all resided in shallow low-flow areas. At night, the habitat differences amongst adults, apparent during the day, largely disappeared as all fish (irrespective of species and size class) were found in the shallow low flow areas, presumably resting or sleeping.

What is driving these patterns? The finding that the two matrotrophic species inhabit faster-flowing waters relative to the three lecithotrophic species is consistent with our prediction derived from the locomotor performance hypothesis. So, one of our primary conclusions is that reproductive mode (both lecithotrophy versus matrotrophy, and superfetation – the ability of a female to gestate broods at different developmental stages) may be factors that influence microhabitat usage. But this does raise the question as to why it would be advantageous for fish to utilize fast-flowing current, even if they can, given that it likely requires more energy expenditure compared to utilizing low-flow areas of the river. In other words, why do the two matrotrophic species utilize fast-flowing current and deep waters (during the daytime)? We hypothesize that bird predation may be a key explanatory variable. There is some data suggesting that bird (in our case from kingfishers and herons) predation on fish is most effective in shallow stagnant waters, and less effective in deeper, fast-flowing waters. Likewise, birds are likely to favor larger-sized fish (i.e. adult poeciliids). Thus, one could argue that large adult poeciliids may minimize predation during the day-time from birds by inhabiting deep, fast-flowing areas. In contrast, small fish (i.e. juveniles) may minimize predation by moving to the shallows (to avoid predation by large fish in deeper water). Here, in the shallows, they are also presumably not a desirable prey item for large birds, due to their very small size (<2 cm). Furthermore, juveniles of all species are small and have poorer swimming performance compared to adults, and may thus be constrained to inhabiting low-flow regions. In sum, adults of matrotrophic species may be capable of inhabiting fast-flowing waters due to reproductive adaptations, and they do so because it represents an adaptive response to avoid bird predation in the shallow slow-flowing water. (It is also possible that they move to deep fast-flowing waters to exploit food resources and minimize competition with the other poeciliid species). At night, habitat differences largely disappear as everyone moves into the shallow, low-flow areas. We suggest, based on observing that the fish are largely immobile and appear to be resting or sleeping, that this may be a functional constraint; fish may move out of the fast-current while resting to avoid being swept away.

What are the implications of this work? In the paper we state: “Our study can be seen as a first step on which future, ideally experimental, studies can build to assess the costs of locomotion as a function of reproductive mode and pregnancy state. Future studies should furthermore focus on comparing microhabitat use in more live-bearing fish (e.g. from the family Poeciliidae, Anablepidae, Goodeidae, or Zenarchopteridae), but also other aquatic live-bearing animals (e.g. amphibians, reptiles, and mammals), to assess the generality of these findings.”

Finally, I wanted to share some things learned while conducting tropical fieldwork that may be useful for others. First, when in the tropics it is definitely worthwhile exploring for wildlife at night using a headlamp. This is particularly true around water (i.e. streams, rivers, wetlands, ponds). The wildlife you see at night is totally different than what you see during the day – the night belongs to the amphibians, reptiles, and invertebrates. Simply put you see frogs, snakes, and other interesting natural history phenomena that you do not see during the day.

Another is that snorkeling in rivers is amazing and probably greatly underappreciated. Before conducting fieldwork in Costa Rica, I thought of snorkeling primarily as an activity to be conducted in the ocean when on holiday. Now, whenever and wherever I travel, I bring my mask and snorkel. You might think that in order to snorkel effectively there must be no current and the water must be reasonably deep. Neither is true. You can snorkel in very fast current and have great visibility and in surprisingly shallow water. Snorkeling in very fast-flowing waters is actually highly beneficial because in such cases you can see almost nothing while standing above and looking into the water, but as soon as you put your face in a whole underwater world becomes visible. Furthermore, you can effectively snorkel in water that is only a few inches deep with your body lying on the ground; as long as your mask is underwater, you are good to go.

Snorkeling is a great method to characterize a fish community by determining which species are present. A lot of our work in Costa Rica required determining whether a given fish community was high or low predation (i.e. whether predatory species such as Gobiomorus or Eleotris were present). The traditional way of doing this involves some combination of using a seine net and/or cast net to survey the fish community. However, I would argue that snorkeling is the superior method, and would go as far as saying that 5-minutes of snorkeling in a given site is worth an hour of seine or cast netting. A big reason is that with snorkeling you have the advantage of being able to quickly survey large areas and look into areas where it is difficult to use a seine or cast net to detect species (i.e. undercut banks, next to logs, fast current, etc.). Furthermore, with snorkeling you get to see the fish in their natural environment including some amazing underwater scenes.