Burmese pythons, green iguanas, bullseye snakehead, peacock bass……and the list goes on. Florida seems to be the epicenter for introduced species in the United States. Since moving to South Florida at the beginning of the year I have been amazed at the number and diversity of introduced species, and nowhere is this more evident than with reptiles and freshwater fish. I spend a lot of time outdoors and the three most common species of reptile I see in the greater Miami area are brown anoles (native to the Caribbean), green iguanas (native to Central and South America), and curly-tailed lizards (native to the Caribbean).

Green Iguana

Northern Curly-tailed Lizard

Brown Anole

Black Ctenosaur

African Rainbow Lizard

A sampling of Florida’s introduced reptile species.

Likewise, when fishing I am more likely to catch introduced butterfly peacock bass (native to South America), Mayan cichlid (native to Central America), or Jaguar Guapote (native to Central America) than native species such as largemouth bass.

Sailfin catfish

Hornet tilapia

Oscar

Walking catfish

Butterfly peacock bass

Mayan cichlid

Midas cichlid

Blue tilapia

Snakehead

Spotted tilapia

African jewelfish

Pike killifish

Jaguar guapote

A sampling of Florida’s introduced freshwater fish species.

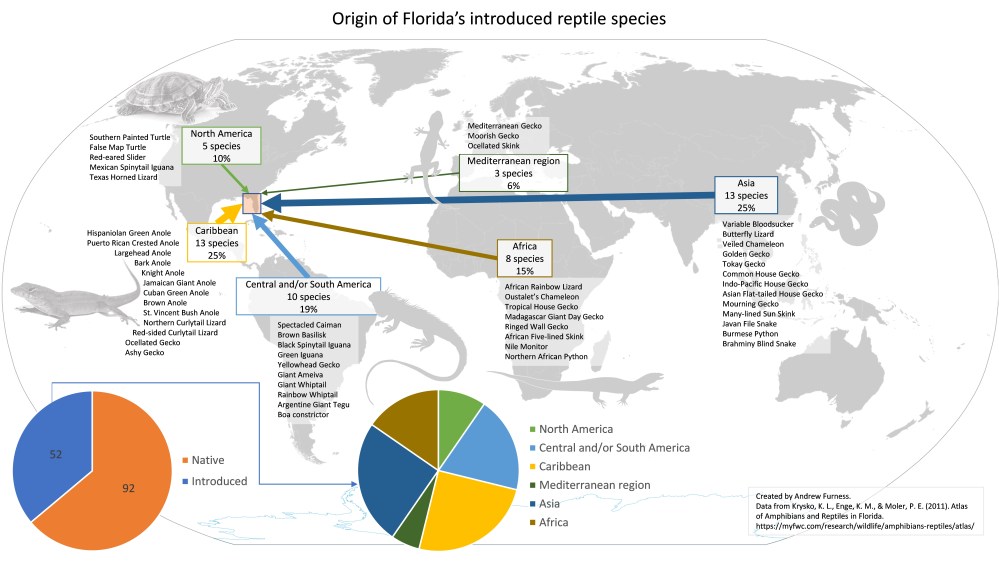

Whenever I encounter and photograph a new species of reptile or freshwater fish I always look up information to see what geographic region the species originally came from (as well as other natural history information). This got me thinking about aggregating this ‘origin of introduced species data’ and displaying it on a world map – thus giving a visual depiction of where in the world Florida’s fish and reptile species originate from. And this is what I did.

The geographic origin of Florida’s introduced and established (reproducing) nonindigenous freshwater fish species. Data was taken from the book: Robins, R. H., Page, L. M., Williams, J. D., Randall, Z. S., & Sheehy, G. E. (2019). Fishes in the fresh waters of Florida: An identification guide and atlas. University Press of Florida.

The geographic origin of non-native reptile species found in Florida. Data was taken from Appendix A of Krysko, K. L., Enge, K. M., & Moler, P. E. (2011). Atlas of Amphibians and Reptiles in Florida. https://myfwc.com/research/wildlife/amphibians-reptiles/atlas/

A few key patterns jump out from the above figures. The first is that introduced species make up a rather large fraction of the total. Specifically, more than a quarter of freshwater fish species (48/169 or 28%) and over a third of reptile species (52/144 or 36%) have been introduced from other regions of the globe. I’d imagine that this is the highest of any state in the U.S.A. (with the possible exception of Hawaii). I grew up in Wisconsin and cannot think of a single introduced reptile species in my home state, and amongst freshwater fish only the common carp comes immediately to mind. It might be interesting to compile such data for other states and test various predictors of the number of introduced species, including climate and human population density.

I’d venture to guess that a confluence of factors make Florida particularly prone to species being introduced and becoming established (and frequently having a detrimental ecological impact, i.e. becoming invasive). South Florida has a tropical climate, allowing species from the Caribbean, Central America, South America, Africa, and Asia to become established that wouldn’t be able to survive the cold winters, or at least occasional cold snaps, almost anywhere else in the United States. Florida is the third most populous state (after California and Texas) and has a large trade in exotic pets. Intentional release (by pet owners or private individuals) appears to be a common route to establishment for both freshwater fish and reptiles. Unintentional escape (from the homes of pet owners, pet shops, and zoos) is probably more common for reptiles. However, unintentional escape from outdoor aquaculture facilities appears unique to fish. Florida has many outdoor commercial fish farms, in which fish are raised for food (i.e. numerous tilapia species) and to supply the aquarium trade (i.e. many cichlid species). Flooding during hurricanes has resulted in the release of fish into the extensive canal system that crisscrosses the landscape. Furthermore, some species of fish have been deliberately introduced to create recreational fisheries and commercial opportunities; for example, the butterfly peacock bass was introduced in the mid-1980s by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and subsequently has become established in South Florida. Finally, South Florida is a trading and commercial hub for Latin America and the Caribbean. Many Anolis lizard species from the Caribbean have made their way to Florida as unintentional stowaways on ships transporting ornamental plants or other cargo; this mode of transport appears exceedingly unlikely for freshwater fish.

The geographic sources of introduced species in Florida appear similar for fish and reptiles. Tropical regions across the globe (Central and South America, Africa, and Asia) are all well represented. The one notable exception is that Caribbean islands have been a major source of introduced reptile species, but no freshwater fish species (discussed below). Another common pattern, is the lack of introductions from Australia (and very few from Europe). Specifically, not a single species of fish or reptile has been introduced from Australia into Florida. What explains this pattern? As an island, and a rather dry one, the lack of freshwater fish colonization’s from Australia to Florida isn’t entirely unsurprising. Australia appears to have comparatively few native freshwater fish species and therefore is much more likely to be the recipient of introduced species than a source of them. But Australia does have a large number of reptile species. I am not sure what explains the lack of reptile introductions to Florida, but perhaps it is a combination of the dry climate over most of the continent being a poor match with Florida’s humid climate and hence preventing establishment, not many Australian species being kept in captivity, and/or the large geographic distance between Australia and Florida effectively eliminating unintentional transport amongst traded goods as a route of colonization. There is a similar lack of introduced species originating from Europe. Only the common carp from Eurasia and three species of lizard (two geckos and a skink) native to the Mediterranean region more broadly (including southern Europe, the Middle east, and Northern Africa) have been introduced to Florida. Again, perhaps this pattern is explained by a relatively depauperate reptile and fish community at high European latitude (relative to high species diversity in the tropics), not many European fish and reptile species being commonly kept in captivity, and climate mismatch.

Caribbean islands have been the source of 13 introduced reptiles (all lizards), but no freshwater fish. This pattern is driven mostly by Anolis lizards, which have undergone an adaptive radiation on Caribbean islands. Furthermore, the freshwater fish community of the Caribbean is not very large. Thus, as is the case with another island, Australia, the lack of freshwater fish colonization’s from this region is unsurprising. Both the commonness of reptile species and the rareness of freshwater fish on islands is interpretable based on evolutionary and biogeographic principles. Islands feature prominently in evolutionary theory dating back to Darwin’s Origin of Species. Certain groups of animals are more common amongst island faunas (i.e. birds, bats, reptiles) while other groups less so (i.e. amphibians, freshwater fish). The above is of course a generalization with factors such as island size, island origin (breakaway from a continent versus rise volcanically from the ocean), and distance from the mainland all influencing species richness. Rather than remaining static, island faunas are generated over time through the process of colonization from the nearest mainland (or larger islands), extinction, and in situ speciation – when, over time, a single species splits into two that are reproductively isolated. Taxonomic groups differ in their ability to disperse to and hence successfully colonize islands. Good dispersers are capable of surviving open ocean journeys. Amphibians, with their permeable skin and reliance on freshwater, have a hard time making such journeys. Likewise, saltwater represents a significant barrier to dispersal for primary freshwater fish species. (Incidentally, this likely explains why the freshwater fish that do take up residence on islands tend to be brackish tolerant species or marine species that secondarily colonize freshwater.) Flying animals including birds, bats, and insects can more readily make the journey from mainland to island compared to their terrestrial counterparts. Reptiles, with their tolerance of dry conditions are comparatively well-suited to making open ocean journeys, for example by floating on rafts of vegetation. For more on the fascinating subject of biogeography, I highly recommend the book The Monkey’s Voyage: How Improbable Journeys Shaped the History of Life.

I realize that the same type of graphic could be generated for other groups of introduced vertebrates in Florida (i.e. amphibians, birds, mammals). In fact, I started to make one for amphibians but quickly realized that there are only 3 introduced species in Florida: the Cane toad (Rhinella marina) native to Central and South America, the Greenhouse frog (Eleutherodactylus planirostris) native to the Caribbean, and the Cuban treefrog (Osteopilus septentrionalis) native to the Caribbean. Thus, given the limited number of amphibian species, making a graphic didn’t seem worthwhile. Perhaps if I can find the relevant data, I will make such a graphic for Florida’s introduced birds and mammals and make this the subject of a future post.